PICADILLY PALARE WAS JUST SILLY SLANG

I can't be the first one to make this joke, but iPod owners are the new pod people. I spotted two other pod people today. You can tell by the little white control pieces we have stuffed in our ears. Steve Jobs was beaming me messages all day!

Then again, I sure was glad to have it today when I went out to the NW Film Center to see a screening of the 1929 silent film Picadilly. Little did I know, when they said silent, they meant silent. The movie was being shown with no accompanying music whatsoever. Now, I know a lot of movies from the era have no official score, but it was more common than not that some sort of organist was playing along (my silent film fan friends can correct me if I'm wrong--Elin? Chynna? (yes, it's usually stylish chicks that dig silent films)) in the theatre. So, I whipped out my iPod and loaded up some Bernard Herrmann and Ennio Morricone. I had to skip some obviously inappropriate tracks from Once Upon A Time In The West, but it mainly worked out well. I can't imagine sitting in silence for 107 minutes. It'd kill me!

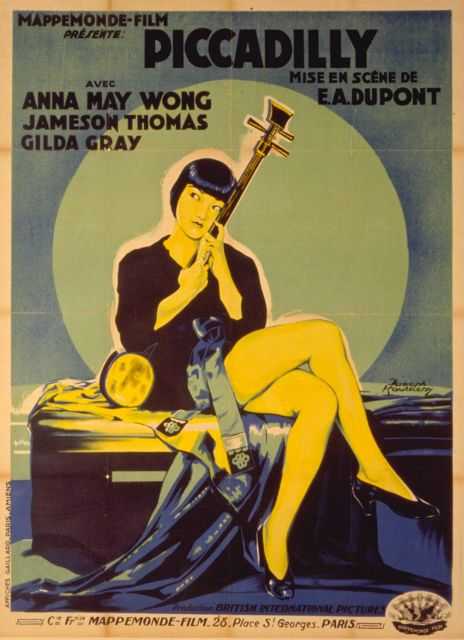

Directed by Ewald André Dupont, Picadilly is a wonderful film. It stars Gilda Gray and the inappropriately second-billed Anna May Wong as dueling dancing divas in a British night club. After the night club owner (played by Jameson Thomas, and you know the character is a Lothario, he's named Valentine) fires Gray's dancing partner because he clearly can't keep his hands to himself, attendance goes down. Thomas stumbles on the idea of having Wong's character, Shosho, take a slot on the dancefloor, having seen her entertain her fellow workers in the kitchen. In doing so, he inadvertently starts an early film catfight that predates All About Eve and similar tales of starlets who don't want to stare the spotlight.

Thomas becomes the object of a dance of seduction between Gray and Wong, both of whom know how to use their feminine sexuality to get what they want from men. Wong is the more aggressive, and thus the more successful, and quickly supplants Gray as the top performer on the circuit. But it's her boldness that will also be her downfall, as she keeps her musical accompanist, a Chinese man named Jim (King Ho-Chang), on her sultry hook, as well, and he doesn't like the competition from Thomas any more than Gray likes it from Wong. And when I refer to a "dance of seduction," I am speaking in a broad metaphor, as the word "dance," and the act itself, stands in for sex in the less-open '20s. The final straw for Gray is discovering that Thomas got a private performance from Wong late at night in his office, and Jim's discovery of a Buddha he had given Wong on Thomas' desk is all he needs to realize the same thing.

By the time Thomas and Wong go out on an actual date, Wong's victory is a foregone conflusion. Wishing to avoid being seen, they head to a lower-class, workman's pub, where their fancy dress clearly puts them out of place. They refer to the bar as their own personal Picadilly, as voluptuous women dance without restraint for the hooting and hollering patrons. Down in this part of town, they don't bother with pussyfooting around the issue, they simply get down and boogie. However, even here, there is a warning for our couple. When a white woman dances with a black man, this is going too far. They are chastised and pretty much chased from the bar. It's a clear signal that Wong and Thomas should tread carefully, and though they see it to a degree, exiting the pub, they quickly forget it as they head upstairs to Wong's apartment.

Here follows a series of wonderful sequences, as Wong places the key to her door in Thomas's hand. There is only a moment for eye contact, for the meaning of the gift to be clear, before a truck passes, covering the new lovers for a moment. Once it's gone, so are they.

Upstairs, Wong continues her dance. She removes all faculty for reason from her quarry via very simple movements, covering and uncovering her face with her lacey sleeve. It's extremely erotic, and the kiss that seals the deal feels absolutely redundant. Wong is now the biggest star at the Picadilly night club.

At this point, though, Dupont is also doing a dance with the viewer as well, moving between the apartment and the street, from the seduction to a woman's shadow cast over the entrance to the building, waiting for the dalliance to end. It is, of course, Gray. Holding a pistol, she has a well-choreographed argument with the dagger-wielding Wong. Both women wear some sort of shield in front of their faces--Gray has a veil on her hat, Wong again using her sleeve--perhaps suggesting that, generally, the faces they show are not the real ones they wear; they are keeping their true nature from view, masking it with a gorgeous visage. We fade to black before either attacks, only to discover by a newspaper headline that the Chinese dancer is dead.

The unheeded warning gives way to real consequences. Sex cost Wong her life, and Thomas is on trial for the murder. It seems clear that he is going to go down for it, too, until Gray shows up and says it was her there that night with his gun, but she blacked out and doesn't know what happened. That's when all eyes turn to Jim. He takes his own life, confessing as it trickles away.

One could choose to read the film in terms of race, and you'd have a pretty good case to say that Picadilly reinforces barriers. It's only the Chinese who pay for this transgression, for stepping out of place. The white couple gets to return to their lives, relatively unscathed. I'd like to give Dupont and the writer, Arnold Bennett, more credit than that, though. I would argue that Picadilly is more of a critique of class.

Though the pub chastises the interracial dancers, there is a familiarity between the black man and the white woman that suggests they mingle at the bar often. Their admonishment has more to do with remembering one's place, possibly only made important by the eyes of outsiders being on them. Thomas is intruding on this scene, and though Wong is from the area, she has left it for coats with fur collars. This idea is lent credence when the couple leave the pub; the white woman is standing outside with a mixed crowd, and as Thomas and Wong pass, she taunts them for their hoity-toity airs. She resents them slumming in her part of London.

The final clue comes in the last shot of the film. We are at a newsstand with papers declaring that the Chinese dancer's Chinese lover killed her and then killed himself. A man buying his paper is unconcerned with the news, more excited that he has won some money on a horse race. As he exits the scene, he is replaced by a parade of homeless-looking men with signs promoting a new show at the Scala called "Life Goes On." They are walking a circle, coming in and out of frame, stuck in the drudgery. Life does indeed go on. The common man continues to toil and suffer, while the upper classes live out their petty dramas unharmed.

For me, beyond seeing a good film, the true discovery is Anna May Wong. The blurb I read on the film before seeing it suggested in some ways there are parallels to her own life and struggles as an Eastern actress in Western movies. Her screen presence is incredible, and it's fitting that one of her most well-known movies is with Marlene Dietrich; if it weren't for the longstanding race hang-ups American culture still suffers from, she'd be remembered in much the same way as her more famous, sex symbol co-star.

Current Soundtrack: misc. mp3s

golightly@confessions123.com * The Website

No comments:

Post a Comment