Anyone know who did this drawing? I took it from here.

It was by some strange coincidence that, earlier this week, just days before the news came out that J.D. Salinger had died, I was contacted on Facebook by an old friend who I hadn't talked to since probably 1992 or thereabouts. She had starred with me in a senior project I had done in high school, playing Franny opposite my Zooey in a video adaptation of the back half of my favorite of Salinger's four books, Franny and Zooey. It was an effort as ambitious as it was amateur. Filming two people talking on the phone is more complicated than you think. Particularly if you consider that my Franny had broken her leg or sprained her ankle or something similar, and we had to shoot her scenes with her sitting in bed, the offending corrective wardrobe buried under her mother's bedspread. We were both in drama and at that time were preparing for a production of Inherit the Wind. I was growing my dyed black hair out to go back to my natural color to play the lawyer Henry Drummond, and I was sporting a tiny ponytail that I tried to tell myself was a samurai-style topknot--something I desperately wanted to hide. In the school play, fittingly enough, Franny played the little girl who, at the end of the first act of Inherit the Wind, sees my character and runs away screaming, "Eeeek! The devil!" Life and its coincidences, life and its ironies.

Finishing the project took a sad turn worthy of Salinger. It took me something like 24 hours to edit the twenty-minute movie, working with my video camera and two VCRs. Even if we'd had a computer at my house, this was well before iMovie, and it was labor intensive, fast forwarding and rewinding to find the right clip, hoping to properly time the jump from pause to record and not get a rough, shaky cut. When I finally emerged from my room, which was tucked away in the garage, I was eager to show someone, and so I grabbed my father. He watched it patiently, and when it was all through, I eagerly looked to him for some kind of approval. He paused, and then spoke in sober, gruff tones. "Do you have to say ‘goddamn' so much?'"

"Well, yes," I whined, "that's the way it is in the book, those aren't my words, those are his words."

He didn't see why I couldn't have censored the language, I couldn't see why he couldn't see how hard I worked. The damage was done. Fittingly, at some point in the future, I had a vivid dream where my father tore up a copy of Catcher in the Rye, ripping it in half like a strongman attacking a phone book. I cried and argued and tried to make him understand that the book was me, he was tearing me in half. As one-sided as the dream was, it led to a teenage epiphany: he and I were so worried about the other guy not understanding us, we never bothered to try to understand one another. We were too caught up in our own junk to realize we were on common ground.

I first read Catcher in the Rye when I was sixteen. I was waiting for a then unrequited girlfriend to get out of some after-school activity she was involved in. I was going to drive her home. A beat-up copy of Salinger's novel, with its all-too-familiar burgundy cover, had been dropped in the school parking lot. I retrieved it from the asphalt and sat on the trunk of my car and read at least half the book before the girl arrived. There was no looking back after that. Like countless other adolescents, I was immediately a best friend of Holden Caulfield. Hell, the book even had a fart joke, that bit about Marsalla ripping one in chapel and really blowing the roof of. Nothing my English teachers ever assigned me had fart jokes.

Portrait by Scott Morse for "Hey Oscar Wilde!"

For all the talk of Fitzgerald and Hemingway that dominated my college experience, the way they were the polar opposites, the two styles of writing, the lyrical and the manly, with Faulkner in the arty middle (the lit version of the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who; or more currently, Blur, Oasis, and Pulp), I would actually argue that no 20th Century American Author had a more profound and ubiquitous influence than J.D. Salinger. I learned a great deal from him, developed my love for italics and for hyperactive speech from reading his books. Every author whose debut novel is a first-person narrative about a transition out of innocence is really just covering Catcher in the Rye the way other kids sat in their garage and tried to learn how to play "Satisfaction." Without Holden Caulfield, let's be honest, there would be no Cut My Hair

When you know Salinger's work you will begin to see it everywhere. It's like a secret language. Fans lay coded messages for other fans to find. Nick Hornby owes a pretty obvious debt, for instance. Wes Anderson is the most notorious admirer, his Tenenbaums being his own version of the Glass family, the child prodigies that run through all of his post-Catcher stories. I've also always suspected that William H. Macy's Donnie the Whiz Kid in Magnolia was Paul Thomas Anderson's nod to Zooey's talk about how the Glass children were quiz show regulars. Of course, I've never made a secret of my own reverence of those tales. It's what gave birth to the shared universe of my novels.

That's actually one aspect of Salinger's writing that I don't think gets enough consideration: his creation of a complete world. Much is always made of his conversational prose and his acute understanding of existential angst, but people don't talk as much about the way his books come as a complete, immersive, insular environment. The Glasses and Holden exist in a real, recognizable world, but it's one they've terraformed to fit their peculiarities. It's as if they occupy a definite spot on a map, and within their personal perimeter, everything is molded to their philosophy and their aesthetics, and beyond those lines lies the rest of society, with their screwed-up ideas and bad taste. This is probably the main thing Wes Anderson has taken from Salinger. It's the way that the Tenenbaums live in New York, but how New York seems to regress in time all around them. Or consider Max Fischer's journey in Rushmore, from a private domain he can control to the inner city where the rest of life grows unruly and wild, with no concern to how he sees things.

Portrait by Mike Allred, also for "Hey Oscar Wilde!"

It's been said that Salinger has been more famous in recent years for not writing than he has for what he'd already wrote. He abandoned the publishing world and polite society in general in 1965, preferring to live a secluded life away from the glare of the public eye. He never published again, though there have been rumors that he has been working the whole time. We don't really know. There has been much said about the legendary old crank and none of it is really verifiable--though I am sure now that the vaults are left unguarded, we will find out. There is even a comprehensive book/documentary project about to be unveiled that, had J.D. not already died, well, the scope of this would kill him. (And if it didn't, the prospect of a Catcher in the Rye movie would. How stupid is Hollywood? Plenty stupid.)

Naturally, I am pretty sympathetic to the man in exile. My own work is full of men who try to run away, to escape, and find some peace alone. It's a theme partially inspired by Salinger, but more of a common ground that I found between him and I (and, to a degree, my own father) than something that I developed because of his work. It would still be there without Salinger's example, but it wouldn't be the same. (Particularly not Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?

And say what you want about his self-chosen banishment, but I think unlike any other author, even moreso than Hemingway's big game hunting and knuckle-dusting or Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis' excesses, J.D. Salinger really did live out his work. Like any number of his characters, he chose to get out of it rather than let the world outside tell him who to be. If I had to pick one theory, I'd say he was a man who saw that his audience and the people who made money off of him were never going to let him grow up. They were never going to allow him to mature, not if they could keep him as the same rebellious adolescent. I'm sure he was asked "When are you going to write another Catcher in the Rye?" more times than there are numbers to count them. Hell, I'm nobody and I've had serious people tell me I needed to write another Cut My Hair and then have no idea why I am offended. As if they'd like to get in a time machine and return to whatever fast food counter they worked behind in the 1990s.*

J.D. Salinger was a man who would not be owned. Think about that before you get too eager to see what he had hidden under his bed. Think about that idiot boss you had once upon a time who demanded more of you than you wanted to give, and then realize that we were all J.D. Salinger's idiot boss and that he told us to get bent. And then remember that he did amazing work, everything we could have asked from him, and it still sits on our bookshelves, ready to be endlessly revisited, always offering more to be discovered. Because when you get to the heart of it, J.D. Salinger never stopped giving, the books never stopped offering up their treasures, we were just too selfish to be content with that. In literary heaven, Holden and Seymour and Franny, they all look at us and despair at how little we learned from their example.

* The analogy is intended as disrespect to the people making the suggestion, not to my book.

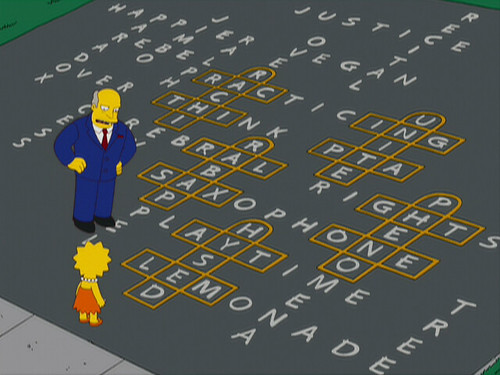

This image was one I hadn't used in a recent review, and it seemed apropos for some reason. Bart Simpson is the more obvious choice for a Holden Caulfield doppelganger, but Bart is not misunderstood, nor does he see through the world's false promises. It's Lisa who no one understands, who has a clear idea of how the world really is, and who sees things in her own way. This image shows not just how she sees things, but her actively trying to impose her sense of order on her environment.

For further reading, here are some never-reprinted short stories from Salinger:

* "Slight Rebellion Off Madison" (1946)

* "Hapworth 16, 1924" (1965)

(Or just jump straight to their full Salinger archive.)

Also, Kim Morgan's "Six Stories: Salinger Inspired Cinema"

And, of course, Catcher in the Rye as pop music:

Current Soundtrack: Radiohead; Bat for Lashes, "Pearl's Dream;" A Camp, "Stronger than Jesus;" The Verve, "Never Wanna See You Cry;" Sister Vanilla, "TOTP;" Brett Anderson, "The Big Time (Live in London);" and too many more to keep track of

e-mail = golightly at confessions123.com * Criterion Confessions * Live Journal Syndication * My Corporate-Owned Space * ComicSpace * Last FM * GoodReads * The Blog Roll [old version] * DVDTalk reviews * My Books On Amazon

All text (c) 2010 Jamie S. Rich