Sly as junk

Strong as death

Sweet as love

Make me dance

Make me sing

Buy you a death's head

Diamond ring"

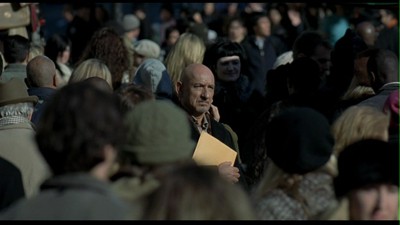

Though normally I don't cross=post full reviews between this blog and DVD Talk, I have decided to post my review of Elegy, the adaptation of The Dying Animal by Philip Roth, here since I reviewed the book last week.

* * *

The art of the movie adaptation is a hot topic at the moment. As I write this, Watchmen is new to theatres, and the comic book blogosphere is ablaze with questions of was it too faithful, was it not faithful enough, and is it even a good movie regardless? While fans of books that get turned into movies are often demanding in their desire for accuracy, the accepted wisdom is generally that in the move from one media to another, changes have to be made to make the story work. What makes a scene come alive on a page is different than what makes it come alive on a movie screen.

One of the arguments for why Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen was unfilmable was that a major subtext of its story and, by its nature, how it was told, was as inherent to and critical of the comic book medium as oxygen is to our continued existence in this atmosphere. I bring this up as the long way around to point out that what makes Philip Roth's 2001 ode to the aging male libido, The Dying Animal, work as a feverish and hypnotic novel is the way it is narrated. The lead character, lecherous professor David Kepesh, relates the story in a breathless manner, speaking to an unseen listener (the reader?), and sharing his reactions and thoughts on what has been happening to him, complete with tangents, flashbacks, and pontifications.

That narration is not gone in its entirety in director Isabel Coixet and screenwriter Nicholas Meyer's 2008 film version, retitled Elegy, but it is significantly pared down, removing the urgency and the disgusting detail of the telling. To get some of that back, they have upgraded the character of poet George O'Hearn (here played by Dennis Hopper) to a more regular confidant for Kepesh (Ben Kingsley), but that still doesn't stave off the shift in the story's tonal quality. The title change, actually, points to a big difference. Elegy suggests something sophisticated, mournful, and reverential to whatever is being honored for its passing; The Dying Animal is primal, unguarded, decomposing, and gross.

The essential story of both book and novel is that Kepesh, a recurring Roth character and both an author and professor, is an aging libertine who uses his classroom as a way to pick up young women. Thinking himself a free and unencumbered sexual being, he is naturally taken aback when the latest object of his lust, the prim and achingly gorgeous Consuela Castillo (Penelope Cruz), so captures him that he finds himself bound to her in ways he would never have allowed in another relationship. He is jealous and needy, and when he can't get over that or his fear of commitment, he drives her away; yet, once she is gone, he remains obsessed.

Entwined in this are the somewhat opposing forces of Kepesh's other lover and his son. The lover, Carolyn (Patricia Clarkson), is another former student, though one Kepesh first bedded in the 1960s. She offers him the kind of sexual relationship he has always clamored for and one that is also more age appropriate, yet even she expects exclusivity. She is freedom with limits, the kind that says don't get too free. On the other hand, his son, Kenny (Peter Sarsgaard), hates his father and his lifestyle, hates what it did to his mother when Kepesh ran out on her, and thus is all the more devastated to discover that he is turning into an adulterer himself. Though, oddly, one who creates a bizarre moral framework to his cheating. He is a philanderer with binding principles, the exact opposite of what daddy strives for.

The story quite delicately brings all these things together--the ideas of personal freedom, sexual desire, and aging--and attempts to show them as linked. Kepesh is not just struggling against the natural decomposition of the human form, but of his ideals. Consuela is young and beautiful, and she also is a test of his intellectual conceits. Next to her, David Kepesh is a pathetic straw man full of insubstantial belief; yet, her own personal problems also bring his philosophy on sex and dying into sharper focus.

Philip Roth is quite often labeled a misogynist, though from my admittedly limited experience with his writing, I'd say that one must stretch their justifications quite far to prove that Roth doesn't fully understand and intend for his reader to see someone like David Kepesh as a creep and a fraud. I didn't see him as a lofty and tragic figure brought down by the evil influence of a woman, but as a man so out of touch with himself as to not understand what he truly needs.

Interesting, then, that this work of macho posturing has been brought to the screen by a female director. Isabel Coixet's previous credits include such challenging works as The Secret Life of Words and My Life Without Me, so she's not afraid of tackling tough, complex subjects. I think it would be easy to suggest that Elegy softens the proselytizing and decreases the bodily fluids from The Dying Animal due to her feminine hand, but I really doubt that is the case. Some of the more foul aspects of the sexual humiliations that pass between Kepesh and Consuela (the trade-off between submission and domination is a major theme) wouldn't make it past the MPAA anyway, the story would have been dialed down regardless. Instead, I think Coixet and Nicholas Meyer--a man, obviously, and no stranger to adapting Roth, having previously penned The Human Stain--are trying to remove some of the harsher aspects of Kepesh's character, the things about him that might repulse the audience when made flesh, so that they might get to the brutal core of his thought processes and turn it into drama. The novel has the benefit of Kepesh's seductive prose to draw the reader in even as his less-than-ideal traits push us away, like peering into a gory wound; the movie, on the other hand, is putting the words into action and doing so without the benefit of a running commentary.

The result is a final product that is more human instead of being so rampantly masculine, more psychologically effecting without being luridly troublesome. The same amount of acid, but perhaps less reflux. This is aided in part by Coixet and director of photography Jean Claude Larrieu's choice to shoot Elegy in a style that is more real than fancy, underlit and often sterile, not quite documentarian but at least seeming to be in a real space. The job is then finished by the remarkable cast. Ben Kingsley plays Kepesh without vanity, letting his age show and slowly allowing the intellectual mask that Kepesh wears over his weaknesses to dissolve.

Arguably, the movie belongs to Penelope Cruz, even if for just achieving the impossible task of wresting the male gaze away from itself and making her character real. In the story's emotional climax, Roth allows Kepesh to "make it all about me," whereas Coixet gives Roth's characters the license to be sensitive in ways the poetic situation demands. Cruz keeps Consuela from being yet another mysterious, idealized woman, but instead makes her a real person. The sympathy we have for her keeps us from having misguided sympathy for Kepesh--the dying animal can really be a beast. Ironically, Coixet also photographs Cruz's body in the most loving and sensual way, making her look as classic and beautiful as the Goya painting David says looks like her. In that, the director manages to portray love in a way Roth never could. The Kepesh of the book can only stare with hungry desire, the author's fetish for verbiage turning every tiny goosebump into a potential sex toy; Coixet's camera shoves Kepesh out of the way and takes a good look for itself, and what it finds waiting is something different and more three-dimensional than what Roth offered up.

That said, Coixet and Meyer do trip over the finish line, creating a coda of redemption that seemingly accepts the cliché of what Hollywood is supposed to do when it adapts a book to the screen. David Kepesh at the end of The Dying Animal is still his own worst enemy, a selfish threat to his own well-being; David Kepesh at the end of Elegy is ready to be the things he spent so long creating a moral philosophy to avoid. Both endings are bittersweet, but the movie version is a tad mawkish. It's salvation that Kepesh hasn't earned, forgiveness without contrition, and though it's not a selling out of sufficient baseness to destroy the movie, it does show that not all Hollywood concessions make for a better adaptation.

The full DVD Talk review, including technical specs and extras.

e-mail = golightly at confessions123.com * Criterion Confessions * Live Journal Syndication * My Corporate-Owned Space * ComicSpace * Last FM * GoodReads * The Blog Roll * DVDTalk reviews * My Books On Amazon

All text (c) 2009 Jamie S. Rich

1 comment:

hey..i linked your blog to min..i hope u dont mind..im trying to linmk all the blogs that start with "confessions of a..."

mine is confessions of a partyphile

Post a Comment